Hello Triangle

The Graphics Pipeline

In OpenGL everything is in 3D space, but the screen and window are a 2D array of pixels so a large part of OpenGL's work is about transforming all 3D coordinates to 2D pixels that fit on your screen. The process of transforming 3D coordinates to 2D pixels is managed by the graphics pipeline of OpenGL. The graphics pipeline can be divided into two large parts: the first transforms your 3D coordinates into 2D coordinates and the second part transforms the 2D coordinates into actual colored pixels. In this tutorial we'll briefly discuss the graphics pipeline and how we can use it to our advantage to create fancy pixels.

The graphics pipeline takes as input a set of 3D coordinates and transforms these to colored 2D pixels on your screen. The graphics pipeline can be divided into several steps where each step requires the output of the previous step as its input. All of these steps are highly specialized (they have one specific function) and can easily be executed in parallel. Because of their parallel nature, graphics cards of today have thousands of small processing cores to quickly process your data within the graphics pipeline by running small programs on the GPU for each step of the pipeline. These small programs are called shaders.

Some of these shaders are configurable by the developer which allows us to write our own shaders to replace the existing default shaders. This gives us much more fine-grained control over specific parts of the pipeline and because they run on the GPU, they can also save us valuable CPU time. Shaders are written in the OpenGL Shading Language (GLSL) and we'll delve more into that in the next tutorial.

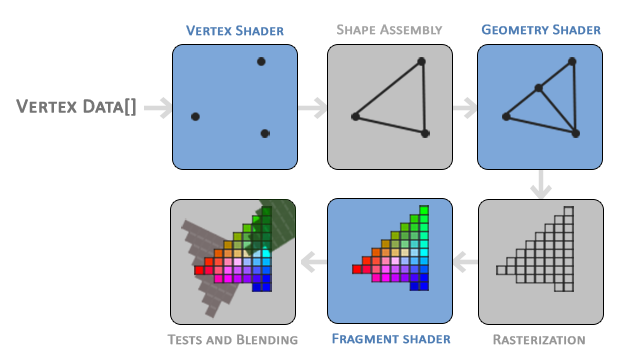

Below you'll find an abstract representation of all the stages of the graphics pipeline.

Sections with a blue background are programmable, and the ones with a gray background can be lightly customized using functions. The stages are as follows:

- Vertex Shader: Vertices are moved into position. This is where things like model position will be applied.

- Shape Assembly. OpenGL works by grouping vertices into triangles; this is the stage where that happens.

- Geometry Shader: An optional stage of the process. Allows you to fine-tune results from Shape Assembly.

- Rasterization: The triangles are converted into fragments.

- Fragment Shader: Fragments are modified to include things such as color data. This is where textures and lighting, among other things, are applied.

- Tests and Blending: The result of the fragment shader is integrated with the rest of the scene.

That may seem like a lot, but it's quite intuitive once setup is complete and we get into the pipeline.

Some new functions

We'll need to override a couple of extra functions to get started. Firstly, we override OnLoad.

protected override void OnLoad()

{

base.OnLoad();

GL.ClearColor(0.2f, 0.3f, 0.3f, 1.0f);

//Code goes here

}

This function runs one time, when the window first opens. Any initialization-related code should go here.

It's also here that we get our first OpenGL function call: GL.ClearColor. This takes four floats, ranging between 0.0f and 1.0f. This decides the color of the window after it gets cleared between frames.

Next, we have OnRenderFrame.

protected override void OnRenderFrame(FrameEventArgs e)

{

base.OnRenderFrame(e);

GL.Clear(ClearBufferMask.ColorBufferBit);

//Code goes here.

SwapBuffers();

}

We have two calls here. Firstly, GL.Clear clears the screen, using the color set in OnLoad. This should always be the first function called when rendering.

Then, we have Context.SwapBuffers. Almost any modern OpenGL context is what's known as "double-buffered". Double-buffering means that there are two areas that OpenGL draws to. In essence: One area is displayed, while the other is being rendered to. Then, when you call SwapBuffers, the two are reversed. A single-buffered context could have issues such as screen tearing.

Next, we have OnFramebufferResize.

protected override void OnFramebufferResize(FramebufferResizeEventArgs e)

{

base.OnFramebufferResize(e);

GL.Viewport(0, 0, e.Width, e.Height);

}

This function runs every time the windows framebuffer gets resized. When this happens the NDC to window coordinate transformation is not automatically updated, causing rendering be done at the old framebuffer size. With GL.Viewport we can update this transformation so that we correctly render to the entire framebuffer.

Vertex input

To start drawing something we have to first give OpenGL some input vertex data. OpenGL is a 3D graphics library so all coordinates that we specify in OpenGL are in 3D (x, y and z coordinate). OpenGL doesn't simply transform all your 3D coordinates to 2D pixels on your screen; OpenGL only processes 3D coordinates when they're in a specific range between -1.0 and 1.0 on all 3 axes (x, y and z). All coordinates within this so called normalized device coordinates range will end up visible on your screen (and all coordinates outside this region won't).

Because we want to render a single triangle we want to specify a total of three vertices with each vertex having a 3D position. We define them in normalized device coordinates (the visible region of OpenGL) in a float array. Put this in your class as a property:

float[] vertices = {

-0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f, //Bottom-left vertex

0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f, //Bottom-right vertex

0.0f, 0.5f, 0.0f //Top vertex

};

Because OpenGL works in 3D space we render a 2D triangle with each vertex having a z coordinate of 0.0. This way the depth of the triangle remains the same making it look like it's 2D.

Normalized Device Coordinates (NDC)

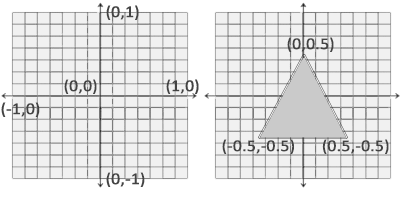

Once your vertex coordinates have been processed in the vertex shader, they should be in normalized device coordinates which is a small space where the x, y and z values vary from -1.0 to 1.0. Any coordinates that fall outside this range will be discarded/clipped and won't be visible on your screen. Below you can see the triangle we specified within normalized device coordinates (ignoring the z axis):

Unlike usual screen coordinates the positive y-axis points in the up-direction and the (0,0) coordinates are at the center of the graph, instead of top-left. Eventually you want all the (transformed) coordinates to end up in this coordinate space, otherwise they won't be visible.

Your NDC coordinates will then be transformed to screen-space coordinates via the viewport transform using the data you provided with GL.Viewport. The resulting screen-space coordinates are then transformed to fragments as inputs to your fragment shader.

Buffers

With the vertex data defined we'd like to send it as input to the first process of the graphics pipeline: the vertex shader. This is done by creating memory on the GPU where we store the vertex data, configure how OpenGL should interpret the memory and specify how to send the data to the graphics card. The vertex shader then processes as much vertices as we tell it to from its memory.

We manage this memory via so called vertex buffer objects (VBO) that can store a large number of vertices in the GPU's memory. The advantage of using those buffer objects is that we can send large batches of data all at once to the graphics card without having to send data one vertex at a time. Sending data to the graphics card from the CPU is relatively slow, so wherever we can, we try to send as much data as possible at once. Once the data is in the graphics card's memory the vertex shader has almost instant access to the vertices making it extremely fast.

A vertex buffer object is our first occurrence of an OpenGL object as we've discussed in the OpenGL tutorial. Just like any object in OpenGL this buffer has a unique ID corresponding to that buffer, so we can generate one with a buffer ID using the GL.GenBuffers function.

Add an int to your Game class to store the handle:

int VertexBufferObject;

Then, in the OnLoad function, put this line:

VertexBufferObject = GL.GenBuffer();

OpenGL has many types of buffer objects and the buffer type of a vertex buffer object is BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer. OpenGL allows us to bind to several buffers at once as long as they have a different buffer type. We can bind the newly created buffer to the BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer target with the GL.BindBuffer function:

GL.BindBuffer(BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer, VertexBufferObject);

From that point on any buffer calls we make (on the BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer target) will be used to configure the currently bound buffer, which is VertexBufferObject. Then we can make a call to GL.BufferData function that copies the previously defined vertex data into the buffer's memory:

GL.BufferData(BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer, vertices.Length * sizeof(float), vertices, BufferUsageHint.StaticDraw);

GL.BufferData is a function specifically targeted to copy user-defined data into the currently-bound buffer. Its first argument is the type of the buffer we want to copy data into: the vertex buffer object currently bound to the BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer target. The second argument specifies the size of the data (in bytes) we want to pass to the buffer; a simple sizeof of the data type, multiplied by the length of the vertices, suffices. The third parameter is the actual data we want to send.

The fourth parameter is a BufferUsageHint, which specifies how we want the graphics card to manage the given data. This can take 3 forms:

StaticDraw: the data will most likely not change at all or very rarely.

DynamicDraw: the data is likely to change a lot.

StreamDraw: the data will change every time it is drawn.

The position data of the triangle does not change and stays the same for every render call so its usage type should best be StaticDraw. If, for instance, one would have a buffer with data that is likely to change frequently, a usage type of DynamicDraw or StreamDraw ensures the graphics card will place the data in memory that allows for faster writes.

Note: After the program ends, all resources used by the process is freed. This means there is no need to delete buffers before closing your program. But if you want to delete buffers for other reasons like limiting VRAM usage, you can do the following:

GL.BindBuffer(BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer, 0);

GL.DeleteBuffer(VertexBufferObject);

Binding a buffer to 0 basically sets it to null, so any calls that modify a buffer without binding one first will result in a crash. This is easier to debug than accidentally modifying a buffer that we didn't want modified.

As of now we stored the vertex data within memory on the graphics card as managed by a vertex buffer object named VBO. Next we want to create a vertex and fragment shader that actually processes this data, so let's start building those.

Shaders

Now that we have our data, it's time to create our pipeline. We do this by creating a vertex shader, and a fragment shader.

The vertex shader is one of the shaders that are programmable by people like us. Modern OpenGL requires that we at least set up a vertex and fragment shader if we want to do some rendering so we will briefly introduce shaders and configure two very simple shaders for drawing our first triangle. In the next tutorial we'll discuss shaders in more detail.

The first thing we need to do is write the vertex shader in the shader language GLSL (OpenGL Shading Language) and then compile this shader so we can use it in our application. Below you'll find the source code of a very basic vertex shader in GLSL:

#version 330 core

layout (location = 0) in vec3 aPosition;

void main()

{

gl_Position = vec4(aPosition, 1.0);

}

Save this as shader.vert.

As you can see, GLSL looks similar to C. Each shader begins with a declaration of its version. Since OpenGL 3.3 and higher the version numbers of GLSL match the version of OpenGL (GLSL version 420 corresponds to OpenGL version 4.2 for example). We also explicitly mention we're using core profile functionality.

Next we declare all the input vertex attributes in the vertex shader with the in keyword. Right now we only care about position data so we only need a single vertex attribute. GLSL has a vector datatype that contains 1 to 4 floats based on its postfix digit. Since each vertex has a 3D coordinate we create a vec3 input variable with the name aPosition. We also specifically set the location of the input variable via layout (location = 0) and you'll later see that why we're going to need that location.

Every shader's entrypoint is the void main() function. This is where you can do any processing you need to. However, here, we simply assign to gl_Position, a built-in variable for vertex shaders that represents the final position of that vertex. However, gl_Position is a vec4, but our input vertices are a vec3. To do this, we use the function vec4 to make the vector long enough.

The current vertex shader is probably the most simple vertex shader we can imagine because we did no processing whatsoever on the input data and simply forwarded it to the shader's output. In real applications the input data is usually not already in normalized device coordinates so we first have to transform the input data to coordinates that fall within OpenGL's visible region

The fragment shader is the second and final shader we're going to create for rendering a triangle. The fragment shader is all about calculating the color output of your pixels. To keep things simple the fragment shader will always output an orange-ish color.

Colors in computer graphics are represented as a vector of 4 values: the red, green, blue and alpha (opacity) component, commonly abbreviated to RGBA. When defining a color in OpenGL or GLSL we set the strength of each component to a value between 0.0 and 1.0. If, for example, we would set red to 1.0f and green to 1.0f we would get a mixture of both colors and get the color yellow. Given those 3 color components we can generate over 16 million different colors!

#version 330 core

out vec4 FragColor;

void main()

{

FragColor = vec4(1.0f, 0.5f, 0.2f, 1.0f);

}

Save this as shader.frag.

The fragment shader only requires one output variable and that is a vector of size 4 that defines the final color output that we should calculate ourselves. We can declare output values with the out keyword, that we here promptly named FragColor. Next we simply assign a vec4 to the color output as an orange color with an alpha value of 1.0 (1.0 being completely opaque).

Compiling the Shaders

We have our shader source, but now we need to compile the shaders. This is done at runtime; pre-compiling a shader and packaging it with your program isn't possible, since the compiled shaders depend on many factors, such as the graphics card model, manufacturer, and driver. Instead, we include the shader source code and compile it when the program begins.

We'll do this by creating a Shader class, which compiles the shaders and wraps several functions we'll see later.

public class Shader

{

int Handle;

public Shader(string vertexPath, string fragmentPath)

{

}

}

The handle will represent the location of our final shader program after it's finished being compiled. We'll do all the initialization in the constructor.

To start off, in the constructor, define two ints: VertexShader and FragmentShader. These are the handles to the individual shaders. They're defined in the constructor because we won't need the individual shaders after the full shader program is finished.

Next, we need to load the source code from the individual shader files. We do that like so:

string VertexShaderSource = File.ReadAllText(vertexPath);

string FragmentShaderSource = File.ReadAllText(fragmentPath);

Then, we generate our shaders, and bind the source code to the shaders.

VertexShader = GL.CreateShader(ShaderType.VertexShader);

GL.ShaderSource(VertexShader, VertexShaderSource);

FragmentShader = GL.CreateShader(ShaderType.FragmentShader);

GL.ShaderSource(FragmentShader, FragmentShaderSource);

Then, we compile the shaders and check for errors.

GL.CompileShader(VertexShader);

GL.GetShader(VertexShader, ShaderParameter.CompileStatus, out int success);

if (success == 0)

{

string infoLog = GL.GetShaderInfoLog(VertexShader);

Console.WriteLine(infoLog);

}

GL.CompileShader(FragmentShader);

GL.GetShader(FragmentShader, ShaderParameter.CompileStatus, out int success);

if (success == 0)

{

string infoLog = GL.GetShaderInfoLog(FragmentShader);

Console.WriteLine(infoLog);

}

If there are any errors when compiling, you can get the debug string with the function GL.GetShaderInfoLog. Assuming there were no issues, we can move on to linking.

Our individual shaders are compiled, but to actually use them, we have to link them together into a program that can be run on the GPU. This is what we mean when we talk about a "shader" from here on out. We do that like this:

Handle = GL.CreateProgram();

GL.AttachShader(Handle, VertexShader);

GL.AttachShader(Handle, FragmentShader);

GL.LinkProgram(Handle);

GL.GetProgram(Handle, GetProgramParameterName.LinkStatus, out int success);

if (success == 0)

{

string infoLog = GL.GetProgramInfoLog(Handle);

Console.WriteLine(infoLog);

}

That's all it takes! Handle is now a usable shader program.

Before we leave the constructor, we should do a little cleanup. The individual vertex and fragment shaders are useless now that they've been linked; the compiled data is copied to the shader program when you link it. You also don't need to have those individual shaders attached to the program; let's detach and then delete them.

GL.DetachShader(Handle, VertexShader);

GL.DetachShader(Handle, FragmentShader);

GL.DeleteShader(FragmentShader);

GL.DeleteShader(VertexShader);

We have a valid shader now, so let's add a way to use it. Add this function to the Shader class:

public void Use()

{

GL.UseProgram(Handle);

}

Lastly, we need to clean up the handle after this class dies. We can't do it in the finalizer due to the Object-Oriented Language Problem. Instead, we'll have to derive from IDisposable, and remember to call Dispose on our shader manually. Below the rest of your code, add the following:

private bool disposedValue = false;

protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

if (!disposedValue)

{

GL.DeleteProgram(Handle);

disposedValue = true;

}

}

~Shader()

{

if (disposedValue == false)

{

Console.WriteLine("GPU Resource leak! Did you forget to call Dispose()?");

}

}

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true);

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

Congratulations! We now have a fully-functional shader class.

Back in your Game class, add a new property, Shader shader;. Then, in OnLoad, add the line shader = new Shader("shader.vert", "shader.frag");. Then, go to the OnUnload, and add the line shader.Dispose();.

Try running; if nothing prints to console, your shaders have compiled correctly!

Linking Vertex Attributes

The vertex shader allows us to specify any input we want in the form of vertex attributes. While this allows for great flexibility, it does mean we have to manually specify what part of our input data goes to which vertex attribute in the vertex shader. This means we have to specify how OpenGL should interpret the vertex data before rendering.

This format information is stored in what is called a Vertex Array Object (VAO). The VAO contains information about the vertex format and what buffers to read from. We will discuss this more shortly, but to get started we create a VAO and bind it like follows:

int VertexArrayObject = GL.GenVertexArray();

GL.BindVertexArray(VertexArrayObject);

With the VAO created and bound, we can start specifying the vertex format and data buffers. To do this we first need to take a look at the format of our vertex buffer.

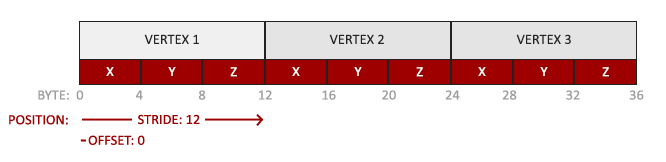

Our vertex buffer data is formatted as follows:

- The position data is stored as 32-bit (4 byte) floating point values.

- Each position is composed of 3 of those values.

- There is no space (or other values) between each set of 3 values. The values are tightly packed in the array.

- The first value in the data is at the beginning of the buffer.

With this knowledge we can tell OpenGL how it should interpret the vertex data (per vertex attribute) using GL.VertexAttribPointer:

GL.VertexAttribPointer(0, 3, VertexAttribPointerType.Float, false, 3 * sizeof(float), 0);

GL.EnableVertexAttribArray(0);

The function GL.VertexAttribPointer has quite a few parameters, so let's carefully walk through them:

- The first parameter specifies which vertex attribute we want to configure. Remember that we specified the location of the position vertex attribute in the vertex shader with

layout (location = 0). This sets the location of the vertex attribute to 0 and since we want to pass data to this vertex attribute, we pass in 0. - The next argument specifies the size of the vertex attribute. The vertex attribute is a vec3 so it is composed of 3 values.

- The third argument specifies the type of the data, which is

float(a vec* in GLSL consists of floating point values). - The next argument specifies if we want the data to be normalized. If we're inputting integer data types (int, byte) and we've set this to

true, the integer data is normalized to 0 (or -1 for signed data) and 1 when converted to float. This is not relevant for us, so we'll leave this as false. - The fifth argument is known as the stride and tells us the space between consecutive vertex attributes. Since the next set of position data is located exactly 3 times the size of a float away we specify that value as the stride. Note that since we know that the array is tightly packed (there is no space between the next vertex attribute value) we could've also specified the stride as 0 to let OpenGL determine the stride (this only works when values are tightly packed). Whenever we have more vertex attributes we have to carefully define the spacing between each vertex attribute but we'll get to see more examples of that later on.

- The last parameter is the offset of where the position data begins in the buffer. Since the position data is at the start of the data array this value is just 0. We will explore this parameter in more detail later on

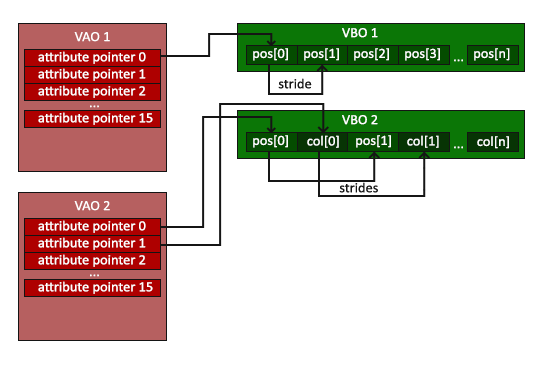

Each vertex attribute takes its data from memory managed by a VBO and which VBO it takes its data from (you can have multiple VBOs) is determined by the VBO currently bound to ArrayBuffer when calling GL.VertexAttribPointer. Since the previously defined VBO is still bound before calling glVertexAttribPointer vertex attribute 0 is now associated with its vertex data.

Now that we specified how OpenGL should interpret the vertex data we should also enable the vertex attribute with GL.EnableVertexAttribArray giving the vertex attribute location as its argument; vertex attributes are disabled by default.

From that point on we have everything set up: we initialized the vertex data in a buffer using a vertex buffer object, set up a vertex and fragment shader and told OpenGL how to link the vertex data to the vertex shader's vertex attributes. Drawing an object in OpenGL would now look something like this:

GL.BindBuffer(BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer, VertexBufferObject);

GL.BufferData(BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer, vertices.Length * sizeof(float), vertices, BufferUsageHint.StaticDraw);

GL.VertexAttribPointer(0, 3, VertexAttribPointerType.Float, false, 3 * sizeof(float), 0);

GL.EnableVertexAttribArray(0);

shader.Use()

// 3. now draw the object

someOpenGLFunctionThatDrawsOurTriangle();

We have to repeat this process every time we want to draw an object. It may not look like that much, but imagine if we have five or more vertex attributes, and perhaps hundreds of different objects (which is not uncommon). Binding the appropriate buffer objects and configuring all vertex attributes for each of those objects quickly becomes a cumbersome process. What if there was some way we could store all these state configurations into an object and simply bind this object to restore its state?

Vertex Array Object

A vertex array object (also known as VAO) can be bound just like a vertex buffer object and any subsequent vertex attribute calls from that point on will be stored inside the VAO. This has the advantage that when configuring vertex attribute pointers you only have to make those calls once and whenever we want to draw the object, we can just bind the corresponding VAO. This makes switching between different vertex data and attribute configurations as easy as binding a different VAO. All the state we just set is stored inside the VAO.

Core OpenGL requires that we use a VAO so it knows what to do with our vertex inputs. If we fail to bind a VAO, OpenGL will most likely refuse to draw anything.

A vertex array object stores the following:

- Calls to

GL.EnableVertexAttribArrayorGL.DisableVertexAttribArray. - Vertex attribute configurations via

GL.VertexAttribPointer. - Vertex buffer objects associated with vertex attributes by calls to

GL.VertexAttribPointer.

The process to generate a VAO looks similiar to that of a VBO. As a property, add

int VertexArrayObject;

Then, in OnLoad, before the call to GL.BindVertexArray, add:

VertexArrayObject = GL.GenVertexArray();

To use a VAO, all you have to do is bind the VAO using glBindVertexArray. From that point on, we should bind/configure the corresponding VBO(s) and attribute pointer(s) and then unbind the VAO for later use. As soon as we want to draw an object, we simply bind the VAO with the prefered settings before drawing the object, and that is it. In code, this would look a bit like this:

// ..:: Initialization code (done once (unless your object frequently changes)) :: ..

// 1. bind Vertex Array Object

GL.BindVertexArray(VertexArrayObject);

// 2. copy our vertices array in a buffer for OpenGL to use

GL.BindBuffer(BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer, VertexBufferObject);

GL.BufferData(BufferTarget.ArrayBuffer, vertices.Length * sizeof(float), vertices, BufferUsageHint.StaticDraw);

// 3. then set our vertex attributes pointers

GL.VertexAttribPointer(0, 3, VertexAttribPointerType.Float, false, 3 * sizeof(float), 0);

GL.EnableVertexAttribArray(0);

Then, to actually draw the object, you'd put the following in your render loop:

GL.UseProgram();

GL.BindVertexArray(VertexArrayObject);

someOpenGLFunctionThatDrawsOurTriangle();

And that is it! Everything we did the last few million pages led up to this moment, a VAO that stores our vertex attribute configuration and which VBO to use. Usually when you have multiple objects you want to draw, you first generate/configure all the VAOs (and thus the required VBO and attribute pointers) and store those for later use. The moment we want to draw one of our objects, we take the corresponding VAO, bind it, then draw the object and unbind the VAO again.

To draw our objects of choice, OpenGL provides us with the GL.DrawArrays function that draws primitives using the currently active shader, the previously defined vertex attribute configuration and with the VBO's vertex data (indirectly bound via the VAO).

shader.Use();

GL.BindVertexArray(VertexArrayObject);

GL.DrawArrays(PrimitiveType.Triangles, 0, 3);

The GL.DrawArrays function takes as its first argument the OpenGL primitive type we would like to draw. Since I said at the start we wanted to draw a triangle, and I don't like lying to you, we pass in PrimitiveType.Triangles. The second argument specifies the starting index of the vertex array we'd like to draw; since we want to draw all of our vertices, we just leave this at 0. The last argument specifies how many vertices we want to draw, which is 3 (we only render 1 triangle from our data, which is exactly 3 vertices long).

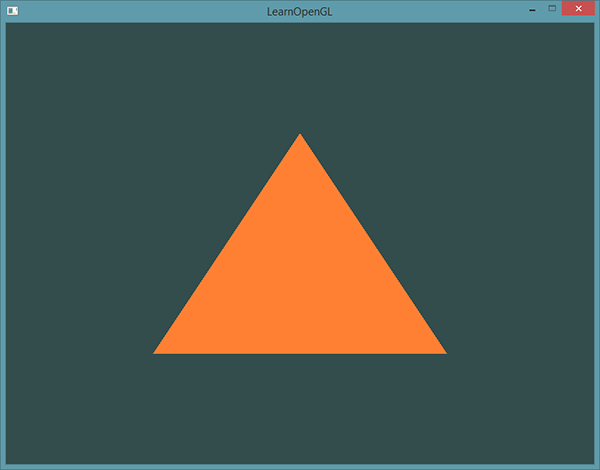

Now try to compile the code and work your way backwards if any errors popped up. As soon as your application compiles, you should see the following result:

The source code for the complete program can be found here.

If your output does not look the same you probably did something wrong along the way so check the complete source code, see if you missed anything or ask in our official Discord server.

Addendum: Dynamically retrieving shader layout

For this example, when we call GL.VertexAttribPointer, we use a hardcoded layout of 0 for the position of our variable. This only works because our input variable in shader.vert explicitly sets the layout to 0. But what if you didn't want to do it that way? You can retrieve the position at runtime, if you so wish.

If you want to do this, add the following function to your Shader class.

public int GetAttribLocation(string attribName)

{

return GL.GetAttribLocation(Handle, attribName);

}

Then, when you're setting up the VAO, you can use shader.GetAttribLocation("aPosition") instead of 0. If you do it this way, you don't have to include the layout(location=0) line in the shader anymore.

This tutorial will stick with hardcoded values, but it's important to know how to do it either way.